The former UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, recently published his memoirs, My Life, Our Times. The 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) coincided with the final stages of Brown’s career as a politician, and politicians today must avoid repeating the mistakes which led to that crisis. This piece explains what caused the GFC and what lessons we can learn from it. I believe those lessons are radically different from those provided by Brown in his memoirs.

Many used the occasion of My Life, Our Times’ publication to praise what they saw as Brown’s achievements:

Although such praise is most often given to Brown as recognition for his government spending initiatives, he was, early on in his career, particularly respected for his fiscal rectitude, earning him the nickname “Iron Chancellor.” Understanding the GFC allows us to see that this early reputation of Brown’s, as well as the spending for which he has recently been praised, were both built on an economic boom fuelled by a debt bubble, and why, when that boom ended, he turned out to have been made not so much of iron, as of raffia.

Many of the silly, irrational economic views prevalent in the media right now – on fiscal stimulus or productivity for example – are rooted in a misunderstanding of the GFC and the sub-prime debt crash which lay at its heart. This piece will hopefully correct some of those misunderstandings.

I will try to explain that you can’t denounce the crazy debt bubble which caused the GFC while hankering after the unsustainable growth that it made possible. You can’t shake your head, knowingly, at the sub-prime bubble, but at the same time yearn, nostalgically, for the growth that came with it. You can’t have one without the other.

1: Recycled Asian exports

It may seem odd to start with Asian exports, but the GFC’s inception came at a time when unprecedented quantities of Asian countries’ (mainly China’s) trade surpluses with the US were recycled into US treasuries to prevent their currencies from appreciating against the dollar. This can be seen in two charts:

Foreign reserves are constituted by stocks of foreign currency held at central banks, mainly, in the period covered by this chart, Asian central bank reserves of US dollars held in the form of US treasuries. This sum increased roughly 3.5x from 2003 to 2008, to around $7 trillion. It is hard to get your head around such gigantic figures. One way to put them into some kind of perspective is to compare them to another, similar number. A good benchmark might be the total cross-border holdings of all debt securities by all non-central banks in the world, as recorded by the Bank for International Settlements. These amounted to $6.3 trillion at the end of 2008 (the number has been fairly stable around this level since then). This means that, incredibly, it took just over five years for only the foreign currency component of central bank reserves to increase by ~$5 trillion, ~85% of the $6.3bn total cross-border bond holdings of all the non-central banks in the world.

To put that increase in historical context, it took central banks just over five years to accumulate a full three and a half times the total amount of foreign reserves it took the global system almost a century (ninety years) to accumulate from the foundation of the Federal Reserve in 1913 to 2003.

This growth was the result of the growth in global trade, which generated the export dollars in Asia that were handed over to Asian central banks whose policy was to recycle them into US treasuries (in order to keep their currencies from appreciating). From 2003 to the peak in 2008, the period we focused on in connection with foreign reserve accumulation, the annual amount of global exports increased just under 2.5x to around $17.5 trillion dollars. This is eye watering growth. In five years, exports increased to two and a half times the annual amount it had previously taken centuries to reach. The key date, marked with a red arrow, is the end of 2001, when China joined the WTO. It was this which preceded and led to the breathtaking growth in both exports and foreign currency reserves. At the time, it might have seemed as though easy credit and an abundance of cash had suddenly come out of nowhere. In reality, it was, in large part, a ~$5 trillion blowback effect from China starting to fully participate in global trade for the first time.

At the heart of the growth in exports and foreign currency reserves was a self-reinforcing, circular financial flow. The US would buy imports from Asia for which it paid in dollars. The Asian central banks would use those dollars to buy US treasuries – effectively lending their trade surplus to the US government. This depressed US government borrowing costs relative to what they should have been given the strong economic activity underpinning such voracious importing of Asian goods. That depressed interest rate then allowed people to borrow more cheaply, boosting both consumption and house prices. This boost in turn increased the demand for Asian exports, and so on … US consumption of Asian exports was booming, funded by loans from Asian central banks. As one wise economist I know put it at the time, “every Korean car arrived in the US with an auto loan cheque under the windscreen wiper.”

The relevance of this circular Asian export boom is that it created strong economic growth, abnormally low interest rates and a wall of money looking for a home. It was how the US financial system and its regulators coped with that wall of money which determined the inception of the GFC.

2: US banking leverage ratios

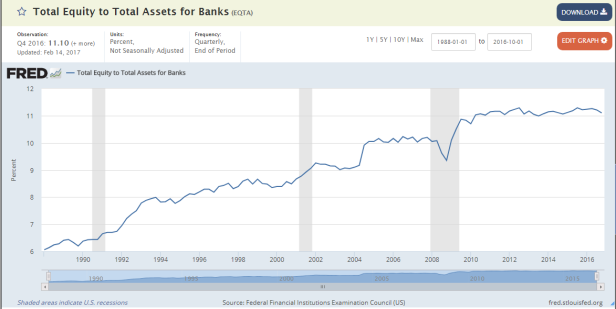

This environment was rocket fuel for the US banking sector. A strong economy with low unemployment and booming house prices kept credit defaults very, very low. And assets, especially the mortgage loan book, were expanding rapidly. In such an environment, banking suddenly seemed like a low risk business. However, on the face of it, it might look as though US banks had entered the crisis having accumulated a prudent level of equity capital relative to their assets. In other words that they weren’t fooled by this benign environment:

Equity to assets is on a continually rising trajectory in this chart from the St Louis Fed, with an apparent one percentage point increase in the ratio in 2004/2005, a few years before the crash. Assuming this isn’t because of an accounting change, the chart might suggest that the banks were, sensibly, increasing equity reserves in the good times ahead of any possible set-back.

However, the picture is more complicated:

- As is well known, US banks were increasingly off-loading or securitising their mortgage loans to investors such as insurance companies and pension funds during this period. So they were able to grow their activity faster than their balance sheet because of appetite from investors to take some of the loans they were writing off their balance sheet. In many cases, although the assets sold to those investors went off balance sheet in accounting terms, the banks had sold them with assurances that they would support the products in which those assets were wrapped. In other words they could come back on balance sheet if things were to go sour;

- The US banking sector had gone through a massive merger and acquisition (M&A) binge and a lot of the equity on its balance sheet was goodwill, or an accounting entry for the premium over net asset value (i.e. book value) that had been paid for acquisitions, and not any reflection of any capital injected by investors or retained profit. Unfortunately, you can’t use goodwill to pay the people queuing up outside Northern Rock;

- The quality of the loan book was rapidly deteriorating as more and more highly leveraged mortgages were written on more and more unaffordable homes. Whatever was happening to the equity the banks held against the money they were lending, the people borrowing from them had an increasingly small or sometimes non-existent amount of their own wealth securing the loan. So the value of the loans which remained on the banks’ balance sheets was overstated. Had this been correctly provisioned for, their equity ratios would have looked much worse.

This can be seen, albeit obliquely, in the c. 0.5% fall in the equity ratio in 2008. The optically small fall happened despite a massive injection of fresh equity, mainly by the US government and the Federal Reserve, into the US banking system. This equity injection hides what the dramatic decline of that ratio would have been had it reflected an adjustment to a realistic valuation of the banks’ equity and assets.

The impact of low government bond yields was therefore amplified by bank equity capital ratios which, in reality, were not keeping up with the growth in their balance sheet risk. This created a powerful banking multiplier effect which poured fuel on the flames of the recycled Asian trade surplus.

You can see the combined result of the recycled Asian surplus and the banking multiplier effect vividly in the BIS data for total global cross-border financial claims of banks (this series includes the banks’ loans as well as their ~$6.3bn bond holdings discussed above), which jumped by $25 trillion, a staggering amount even in the context of the huge numbers we have considered so far. To put the figure into perspective, the annual GDP of the USA and the EU combined before China’s WTO entry was ~$20 trillion. In other words, the increase in cross-border bank claims from China’s WTO accession to the peak of the GFC was enough to double the GDP of the USA and the EU combined and leave ~$5 trillion in change.

To put that increase in historical context, the increase in the seven years from China’s entry into the WTO to the peak of the GFC is equal to 2.5 times the total cross-border financial claims accumulated by banks since the first bank was founded (in medieval Italy, dixit Wikepedia). In seven years you get two and a half times the growth which had previously taken more than seven centuries to achieve! You might have thought that this would have raised a few questions about the sustainability of the benign conditions which accompanied such a massive and unprecedented growth in debt …

3: Derivatives

Unfortunately, this over-leverage was not restricted to bank loans. Michael Lewis’ The Big Short (2011) focuses on Credit Default Swaps (“CDS”), a kind of financial insurance product, as a central cause of the GFC. At the epicenter of the GFC were sub-prime loans, effectively mortgage loans to borrowers who were too poor to afford the houses they lived in, and which would turn sour if property prices ever stopped going up. Naturally, there was great demand for insurance against defaults on the various classes of sub-prime debt from a number of entities: the banks writing the mortgages, financial institutions to whom (as we saw above) those mortgages were repackaged and sold in the form of CDOs, CLOs etc. and, crucially, the heroes of The Big Short who thought the whole thing was a fraud. These entities went into the CDS market either to hedge their credit risk or (in the case of the heroes of the Big Short) to make money when the house of cards collapsed.

On the other side of that trade were the villains of The Big Short, insurers like AIG and Wall Street brokers like Goldman and Morgan Stanley, who thought it was easy money to take juicy premiums against the risk of sub-prime default – a risk they underestimated. When property prices eventually stopped rising and mortgages on variable rates (“ARM”) with two year teaser rates re-set to higher market rates, mortgage defaults exploded and a lot of the CDS “credit insurance policies” were triggered. The problem was that by the time this crash happened the derivatives market was gigantic. And the contracts in it were so complex that the extent of the risk they represented was not understood. Warren Buffett, devastatingly, and, as so often, ahead of the game, called them “weapons of mass destruction” in Berkshire Hathaway’s 2003 annual report.

The companies writing the insurance turned out not to have nearly enough capital and were therefore unable to pay out; they were caught with their trousers down. Not only was there a lack of equity capital backing the loans that banks were making, there was also insufficient equity capital backing the commitments they (and insurers like AIG) had made for the CDSs and other derivatives they had written. The banks and insurers’ insouciance about their CDS exposure was a result of the the wall of money and ultra-benign conditions created by the recycled Asian export effect and the insufficiently high banking equity ratios; it seemed impossible that defaults might occur in such boom times. That insouciance in turn allowed many lenders (or investors) to be more insouciant about the loans they were writing (or buying from lenders), thinking their credit risk had been insured.

Many wrongly pin the blame for the GFC entirely on the “madness” of the sub-prime debt market, as if, somehow, everything would have been ok had people just not invested in this toxic stuff. In other words, according to this reading of the GFC, we could have had the massive leverage boom (due to the recycled Asian trade surplus and the low banking equity ratios), but somehow decided to take a pass on those pesky CDOs. A gigantic, unprecedented increase in debt … but without any crazy investments. As if. The analysis of the GFC in this post, on the contrary, demonstrates that the different factors which caused the GFC made investments in speculative assets like sub-prime bonds inevitable. The massive wall of money described above needed to be invested – somewhere! Had it not been sub-prime debt, it would have been something else. Returns on normal investments such as government bonds, quality corporates or shares were abnormally low. At the same time, a doped economy meant that even the flakiest business model looked sustainable; a rising tide was lifting all ships. In this environment, it was all but impossible for the market not to invest its cash surplus in the few instruments which offered an attractive yield and seemed to be low risk (in that environment). Sub-prime debt was not the root cause but merely an acute symptom of the GFC.

Despite being incredibly risky, the CDS market was not supported by any Clearing Houses or CCPs, which, in effect, “reinsure” the credit default insurance. The investment banks were trading directly with each other, relying solely on their counterparty’s financial strength. When that financial strength turned out to be only a fraction of what was required to pay out on the credit default insurance, there was a domino effect: Wall Street bank A had bought insurance from Wall Street bank B, but Wall Street bank B couldn’t pay out so Wall Street bank A couldn’t make good on the insurance it had sold to Wall Street bank C, and so on. Two early casualties of this hot mess were Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. As Buffet succinctly put it with his usual barbed wit, “when the tide goes out you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

4: Credit ratings

As is also well known, the ratings agencies such as S&P and Fitch gave AAA ratings to CDOs which consisted entirely of loans that would never be repaid. This was the result of the long term bull market in property in which house prices in one part of the country were uncorrelated with those in another. Not only was it hard to imagine the property market falling anywhere, it also seemed that the market was diversified, and that any potential losses in one part of the property market would be offset by gains in another, making it less risky. This of course turned out to be a deadly illusion. Behind this confidence in the property market was, again, the atmosphere created by the recycled Asian export boom and easy money from the banks – which made it easy for the ratings agencies to think that default risk had disappeared. In addition, the ratings agencies made more money if they rated more products, so they had an incentive to hand good ratings out like confetti.

It was those apparently bullet proof credit ratings which encouraged the insurers and other investors to buy re-packaged assets from the banks (“they’re rated AAA after all!”), thereby enabling the banks to make more loans without growing their balance sheet. And it was also those credit ratings which encouraged the investment banks and insurers like AIG to write so many dangerous CDS contracts (“it’s a AAA credit after all!”). Those CDS contracts also encouraged insurers and other investors to buy more re-packaged assets from the banks, thinking that – hey, their credit risk had been hedged, after all! The ability to hedge credit risk then encouraged banks to write more loans, which in turn encouraged the ratings agencies to rate more bonds …

In other words, the financial sector’s own circular, self-reinforcing system of securities and guarantees was a ghoulish mirror of and super-imposed itself upon the circular, self-reinforcing system of recycled Asian trade surpluses. It was a Ponzi scheme fed by another Ponzi scheme.

5: The Greenspan put

It would be remiss to write about this sorry saga without giving due credit to the former Enron attorney and chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, for his role as éminence grise or Svengali of the system that made it possible. Greenspan, notoriously, thought that invisible hand market forces would correct any imbalances in the market, such as the sub-prime bubble eventually proved itself to constitute. What he ignored was the extent to which the sub-prime boom was the result of very political, mercantilist, Asian central bank policies conjugated with the light equity capital requirements imposed by Greenspan himself on the banks he was purportedly supervising. His dogmatic belief in the market’s ability to auto-correct itself led him to underestimate the system’s vulnerability, as a result of which he allowed banks and others to operate with insufficient capital. Despite this, Greenspan was happy to intervene by cutting interest rates whenever stock markets fell (thus seeming to provide a support level for the markets which was dubbed the “Greenspan put”), notably in 1998 following the collapse of the Nobel economist studded LTCM hedge fund, and in 2001 following the collapse of the dotcom bubble. While he zealously endeavored to prop asset prices up, Greenspan took no measures to prevent the dangerous over-leverage of the financial system he was there to oversee. His approach was all carrot and no stick.

Greenspan’s legacy was perpetuated by his successor, Ben Bernanke, who bailed Wall Street banks and insurers out when they were unable to pay up for their stupid CDS bets. The Fed effectively waded out into the sea and handed Wall Street a towel. It makes you weep.

Those who regard the GFC as an example of the dangers of unbridled free market capitalism would do well to remember that the recycling of Asian trade surpluses into US treasuries was a political decision by the Asian countries concerned, and that lax solvency rules, both for loans and derivatives, and the safety net provided to banks by the Federal Reserve and other central banks, were political decisions by the US and other Western countries, in which an unwholesome, incestuous relationship had been allowed to develop between bankers, politicians and regulators (this makes the fact that the current governor and chairman, respectively, of the Bank of England and the ECB are both Goldman Sachs alumni rather unsettling). This incestuous relationship is brilliantly analysed at the end of the 2010 GFC documentary Inside Job. A key – perhaps the key – component of free market capitalism is that market participants have to have “skin in the game,” and be exposed to both gains and losses from their commercial decisions. Many political and regulatory decisions contributed to the GFC; what they have in common is that they allowed market participants to take huge risks and make huge gains without having any skin in the game.

Lessons of the GFC

It is clear that the causes of the GFC can be summarised as follows:

- Debt fuelled growth was extrapolated into the future;

- Artificially low interest rates and strong growth led investors and lenders to misprice risk;

- Unsuitable loans were made to people who couldn’t repay them;

- Banks and other companies were allowed to hold insufficient equity when making loans and writing derivatives;

- This lack of equity encouraged banks and others to take on too many risky loans and derivatives contracts;

- The banks could take these risks with limited downside because the Federal Reserve would bail them out.

Its lessons, in turn, might be summarised as these:

- The GFC was caused by a combination of mad, reckless decisions and one-off, unsustainable factors. No one looks back on it and thinks “that was a smart thing to do”;

- The growth we experienced from 2002-2007 was fuelled by a crazy debt bubble only made possible by those mad decisions and one-off factors, and was therefore largely illusory and completely unsustainable;

- You wouldn’t have had the growth if you didn’t also have the debt bubble. It’s no use bemoaning the one if your economic policies are based on resurrecting the other;

- Anyone in power in the run up to the GFC, like Gordon Brown, looked good as a result of the crazy debt fuelled boom which preceded it, not due to any acumen or “iron” on their part;

- Any comparison of our economy now to the economy then is comparing reality to a mirage;

- Don’t expect those boom times to ever come back. Unless you want to start a massive new institutional Ponzi scheme like the one which caused the GFC (QE anyone?). Any sustainable growth will be lower in the future;

- Although government deficits cannot be said to have “caused” the GFC (there were many other factors), it was certainly foolish and pro-cyclical of politicians like Gordon Brown to allow government debt to GDP to increase during the boom times that preceded it, when strong tax receipts should naturally have led to surpluses which he could have put away – just on the off chance that the growth might prove to be unsustainable;

- Although public spending “on schools and hospitals” cannot be said to have “caused” the GFC (there were many other factors), we can certainly say that most of the public spending growth in the period leading up to it was only possible because of the artificial, unsustainable debt-fuelled boom which did, in the end, cause the GFC;

- Any cuts in public spending post the GFC are not “punishing” anyone for the GFC but merely taking spending back toward the sustainable levels it would have been at, had the debt-fuelled boom that led to the GFC not happened;

- Sorry.

I know I’m very late to this particular story but I’ve just discovered this site – great analysis and insight, especially your thoughts re the City’s so-called vulnerability to Brexit.

I think the analysis here is spot on but, as a former Fixed Income fund manager, I’d just like to add a couple of my own thoughts to the GFC story.

1) the role of Bill Clinton via FNMA/GNMA has been generally under-explored, I think. Political pressure to push sub-prime loans, via the agencies, was pretty intense and the banks felt they had good company, shall we say, in lowering lending standards. In addition, the too-big-to-fail nature of the agencies gave a measure of cover and comfort to investors, even without explicit guarantees.

2) the recycling of Asian exports into western bond markets caused a dramatic fall in yields and, more importantly, a substantial compression and convergence of yields across the credit curve. Fund managers were faced with the dilemma of how to add alpha, versus beta, in such a market. Having sat through many presentations of M/ABS, CDO structures by banks, the analytics and waterfall protections for the higher rated tranches in the securities seemed plausible at the time. Many issuers and structures were not well regarded and most institutional investors had limited exposure even to liquid TBA MBS and other ABS/CDO products, certainly in Europe anyway, in part because investor guidelines were slow to reflect the new products coming on stream.

It was the leveraged investors that really drove the structured markets and the credit insurance markets as well. The banks were very happy to take the fat structuring fees and reduced balance sheet exposure as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

PS. When I replied to your comment WordPress in its wisdom deposited it in the trash. It’s a great comment so I apologise and have duly fished it out. Please don’t take umbrage …

LikeLike

No umbrage (I love that word for some reason!) taken. I see you’ve ‘reopened’ as Kafka’s Castle – keep up the good fight. We’re approaching a tipping point now with Brexit and the ERG’s new plan will, hopefully, move the argument decisively towards a sensible FTA or WTO Brexit!

LikeLike

Charles, my apologies for not responding sooner – I’ve been very busy with the day job and was away on vacation last week (though still intermittently busy with the day job, of course). I appreciate the time you’ve taken to read my blogs and find your comments fascinating. You are spot on with respect to the US agencies and, rather than add anything to the blog, I will let your comment stand as the best exposition of that argument. What is implied, of course, is that government intervention to support the housing market was also a one of the causes of the crisis, which, again, undermines the idea that it demonstrated the weakness of unfettered capitalism. Probably Help To Buy, David Cameron’s lame subsidy for young people to get onto the property ladder, will have a similar effect, albeit on a smaller scale. You are also absolutely right about that forgotten decade, the nineties. The stock market historian can look to the nineties for many things, in particular the last equity bull market to coincide with a dollar bull market before the FAANG led bull market we have experienced post -GFC and for some reason seems to persist despite ridiculous asset valuations. If you take the period post 2001 off the chart, the nineties do show an unprecedented rise in leverage. The only reason you don’t see it in charts incorporating the post-2001 period is that the increase in debt shrinks everything in the previous period – so you need a logarithmic chart. I’m very grateful to you for the detail of how the toxic stuff was sold. I would be interested to know two things. First, you say institutional investors didn’t go for it in a big way but leveraged investors did. I assume these leveraged investors weren’t institutional, but presumably you don’t mean it was retail investors buying this stuff but hedge funds or prop desks or something? Second, I think it was inevitable that this wall of money would find a toxic outlet. All normal asset valuations were pushed up to such a degree that the cash had to go somewhere dangerous. Do you agree, or do you think that the market could, somehow, have avoided this bubble? If you want to stay in touch you might want to follow me on twitter, where my handle is @semperfidem2004 – but note I am currently suspended for calling Owen Jones a “spaz.” I am currently appealing the suspension. Anyway, thanks again for reading – SF

LikeLike