- The City of London is crucial to the UK economy. Many fear that – as a consequence of Brexit – the City will be harmed by a loss of access to the EU single market.

- However if you look at what the City actually does, it is almost impossible to find any activity which requires single market access. Unfortunately for the City’s enemies in the EU, money moves around the world at the push of a button and international finance is very difficult to control.

- The EU banking passport is not a big part of the City’s activities. It might help some companies to provide financial services to retail customers, but nearly all of the City’s transactions in the EU are not with retail customers but with banks and other financial institutions, who are allowed to do business in financial centers outside the EU.

- The City’s key activity, particularly in connection with its exports to the EU, is to help savers invest in assets like equities or bonds. Most investors invest in assets through funds. Most funds managed in the City and sold in Europe are EU authorised “UCITS” funds. The potential loss of UCITS is a much vaunted Brexit risk for the City.

- However UCITS funds, typically issued in Dublin or Luxembourg, are currently managed by fund managers based all over the world, from London to Hong Kong. UCITS has no rules saying that the manager of a UCITS fund must be based in the EU. Post Brexit, there is nothing to stop a City fund manager from issuing a fund in Dublin or Luxembourg which any investor in Europe can buy.

- The City also makes a lot of money from acting as intermediary between investors buying and selling assets. Institutional or professional investors can trade through any broker they want, anywhere they want and on any exchange they want. Europe never has and never will have any say in this.

- Euroclear in London is more of a risk, although this is more related to its need for ECB backing than any potential loss of the financial services passport.

- The City has been under a lot of pressure in certain areas for years – quite independently from Brexit. Brexit is a convenient excuse for some banks to close unprofitable desks.

- On the plus side, Brexit will enable London to benefit from its status as a place where European investors, financiers and companies can find refuge from Brussels’ infernal meddling.

Is Brexit bad for the City?

The City of London is a major employer and contributor to the UK economy and “contributes more tax than any other sector” according to TheCityUK, a high profile campaign group purportedly seeking to promote the City’s interests. The spill-over effect on the UK economy from the dazzling wealth of the City’s employees, though hard to measure precisely, is probably even more important than its direct contribution. When TheCityUK announced its post-Brexit strategy on 19 August 2016, it was widely reported in the media as signalling that it had given up on its “preferred option of full access to the single market.” As much of the City’s activity is with European counterparties (TheCityUK estimates that the City generates “a trade surplus of £19.9bn” with the EU), many – including some Brexit supporters – have argued that Brexit would have a disastrous impact on the City and therefore the UK as a whole.

However what is noticeable about dramatic headlines such as “Brexit Bulletin: Banks Already Plotting City Exodus” or sub-headlines like “The PM cannot please both the City and anti-EU voters” is how light on detail and vague they are. They are often based on anonymous “sources” and invariably contain neither relevant numbers nor any explanation of which activities performed by the City will be affected. Although TheCityUK claims to be an industry body its publications on the topic are similarly light on detail. The Brexit risks it lists on pages 5-7 of its Practitioner’s Guide to Brexit offer a good example:

- It makes the generic claim that “EU membership has benefited the UK by creating the conditions to both expand UK exports and attract foreign direct investment (FDI), particularly in financial business” – but without giving any specific examples;

- It notes that “250 foreign banks operate in London” and highlights the risk to the UK “if these firms were to reconsider their location in the event of a possible Brexit” – but without saying why they might wish to do so;

- It says the UK could lose access to the UCITS funds market – but without explaining how UCITS works or why Brexit might have an impact.

The lack of informed detail in most contributions to this important debate is probably due to the fact that most journalists, like most people, have no idea what the City does or how it does it. That includes business correspondents at the BBC, who are generally clueless on the subject. After the multiple financial crises experienced in the last twenty years one might indeed be tempted to question whether the people working in the City really understand what they’re doing. My aim in this piece is to explain what the City does – in terms which make sense to someone who doesn’t understand the dark arts of finance – and how these activities might conceivably be impacted by Brexit. My view is that they won’t be.

What does the City actually do?

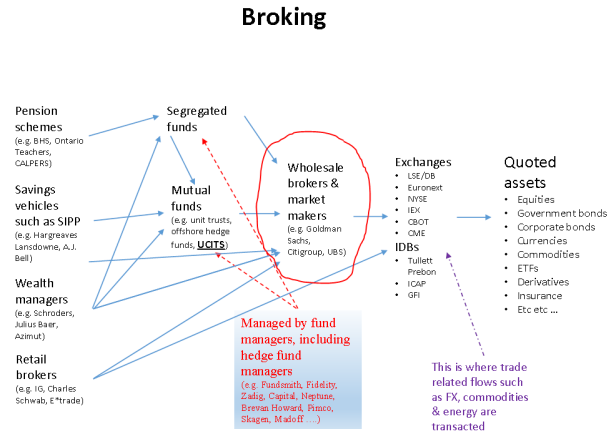

The City’s main activity is to manage financial assets, comprising savings or investments (such as mutual funds) as well as trade flows (such as currencies, trade bills and commodities). Sometimes savings and trade flows intersect, as when pension fund savings are invested in commodity futures that are also used by miners and industrialists to hedge metal prices. The City’s other activities – corporate finance and proprietary trading (“prop trading”) – are also briefly dealt with below. The management of financial assets, as well as corporate finance and prop trading, are all supported by a massive network of related activities: IT support, investment writing, client services and legal and compliance to name only the main ones. But ultimately those support activities are a cost which is funded by the main activities: managing financial assets, corporate finance and prop trading.

Managing financial assets

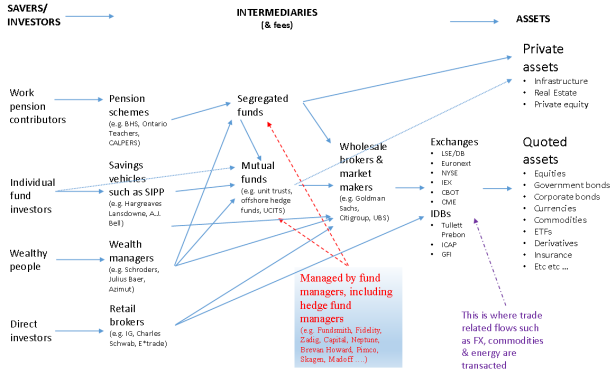

What does managing financial assets mean? Here is a “simplified” diagram, starting with you, the saver or investor.

Finance is the art of passing currency from hand to hand until it finally disappears

Robert W. Sarnoff (1918-1997), President of REC corporation (1948-1975)

This is all very straightforward and intuitive to me, but then I work in the business. Drawing this chart made me realise how complex it must be for some people to understand the City. However it really isn’t that hard. Bear with me, and everything will become clear.

Saver (left hand side) hands over money to buy an asset (right hand side)

Saving or investing involves handing money over and, in exchange for that money, getting a share in an asset which will give you a return. That’s what the savers and investors on the left hand side of the chart are all doing.

The most basic version of that process is handing your money over to your bank and earning (these days virtually no) interest on the deposit. However, to get higher returns, many people invest in longer term assets such as property, equity or bonds – all listed on the right hand side of the chart – which give you a higher return. Or so every investor hopes.

The City sits between the saver and the asset she invests in, earning fees on the way

When the money makes its way from left to right, from the saver or investor to the asset in which she buys a share, it has to pass through a number of intermediaries. You can’t just post a bid for a particular share on eBay after all, or sell your government bonds through the classified ads. Say you decided TJ Maxx (owner of TK Maxx in the UK) was a good investment. Imagine if, to really cut out all the intermediaries, you phoned people at random to find someone with the 150 shares of TJ Maxx you wanted to buy. And let’s assume one of the random punters you phoned miraculously had 150 shares of TJ Maxx that he wanted to sell! What happens next? You transfer the money to his bank account. But what happens if he doesn’t transfer the shares to you? What are you going to do? Maybe you ask him to transfer the shares first. But what happens to him if you don’t transfer the money? Let’s say you meet in a car park, hostage exchange style, where he hands you the certificates and you hand him the cash: how do you prove you bought the shares at that price when you fill out your tax returns?

The financial industry and the City are there to take care of all these details; to ensure the trade is recorded, money transferred from buyer to seller, assets transferred and held in custody, taxes paid (or evaded), dividends or bond coupons received etc. etc. On top of these administrative aspects, there needs to be an efficient way to find a price where buyers are willing to buy and sellers are willing to sell. Every buyer can’t discuss the price of the shares they want to buy with every seller over a cup of tea, as they might do with a second hand car. There has to be an efficient and continuous auction system, which is what a stock exchange is. Most of what the City does is to act as one of the intermediaries who make it possible for savers to invest in assets and, eventually, turn that investment back into cash. At each stage, your money changes hands and a fee (or spread) is paid. By the time it eventually comes back to you, you hope there is something left.

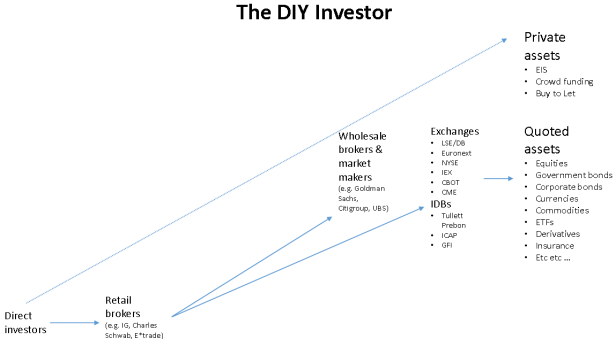

DIY investing: the only way to avoid the City

To simplify things let’s follow the most simple form of investing, what I would call “DIY” investing, represented by the “direct investors” at the bottom of the chart above and reproduced here (I’ve changed the bullet points for “private assets” to show the private or unquoted assets, such as crowd funding, which small investors are able to access and which are typically not available to institutional investors):

In this case, the investor makes all her own decisions, and buys a share in any individual asset she chooses as directly as possible. So she may invest in her cousin’s business via an EIS scheme; buy a flat and rent it out; or open a trading account with IG index and trade in individual company shares or index futures.

The advantage of being a DIY investor is that you pay less in fees. You don’t pay a fund manager or any fund administration expenses for example. You do have to pay some fees however. You need to go through some kind of broker to trade stocks, and that broker in turn has to pay exchange fees. You will also typically buy and sell through a market maker who makes a spread between the bid price at which you can sell to him and the offer price at which you can buy from him. For unquoted investments like real estate or investing in your cousin’s company you will have agency and legal fees. But the bottom line is you do cut out a lot of fees. And online brokerage and exchange fees are very small. If everyone were like this, the City would hardly make a penny.

Most people invest through funds

Despite these cost advantages, most people do not invest like this, for a number of reasons:

- Most people have neither the ability, nor the time, nor the confidence nor even the inclination to do so. For most people investment is like black magic. They would rather hand their money over to a (supposed) professional whom they pay to make investment decisions on their behalf. In the simplest terms, that’s why the City and other financial centers like New York and Hong Kong make so much money – the idea of gambling their savings on the stock exchange makes most people come out in a rash.

- There are significant tax advantages to collective investment vehicles. The money paid into your pension fund, 401k or self-invested pension plan (SIPP) is exempt from income tax (although you have restrictions on when you can withdraw that money, such as having to wait till you reach retirement age to access your pension fund). And any capital gain realised within any fund (such as a pension fund or a UCITS fund) does not suffer capital gains taxes. So the fund can take profits in one asset and reinvest the proceeds into another asset within the fund without being taxed on the gains.

- Collective vehicles enjoy economies of scale with respect to certain costs such as brokerage or custody fees.

Therefore, most savers’ money is invested through funds, rather than directly. This means it has to go through a number of intermediaries.

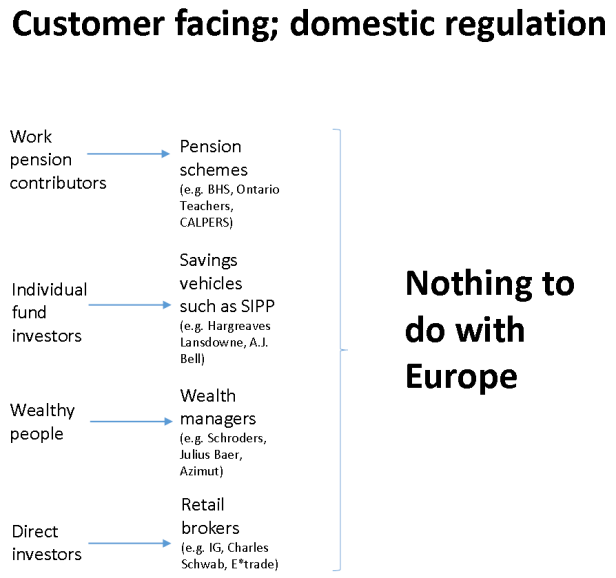

Intermediation, step 1: firms that deal directly with investors are regulated at the nation state level – nothing to do with Europe

At the start of the saver’s money’s journey from left to right we find the entities which first take the money off the saver, and which have a relationship with that saver. Even DIY investors usually need to use such companies. These entities are all on the left hand side of the chart above and reproduced here:

Anyone wanting to receive and take custody of money from an investor will be heavily regulated, but only by domestic regulators. SIPP providers, wealth managers and brokers who cater to individuals are regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK. Pension funds are regulated by the Pensions Regulator in the UK. The EU has nothing to do with any of this. And in fact it is quite a domestic industry. Pensions are a fiercely domestic matter and each country in the EU has its own national pensions regulation.

In theory, what the EU financial services passport does is allow EU customer facing firms authorised by their domestic regulator to be authorised to serve retail customers in other EU markets. Unfortunately, the costs of building a direct to customer operation (sales force, customer service, brand building, marketing and advertising) are so large that very few companies do this in practice. Most of the few that do attempt to offer financial services direct to customers in other EU countries instead buy an existing business which has already sunk those costs and acquired a viable market share. And those companies will, of course, already be approved in that market by the domestic regulator.

Interestingly, the very few personal investment companies that build cross border operations organically (i.e. without acquisitions) in Europe, such as IG or ING direct, and who therefore should in theory be the prime beneficiaries of the EU financial services passport, have to be regulated by the domestic regulator in each market in which they operate. IG Group is one of the – if not the – most successful examples of organic cross border expansion in personal investment in the EU, generating just under £100m in revenue with 35m clients in seven countries in Europe, including Germany, France, Italy and Spain. To put this into perspective, IG’s revenue is a small spread charged on client trades, so the face value of the trades IG handles for European clients is over 100 times its revenue, or around €50m per day. For those of you not fluent in French, this extract from IG’s French website shows that even though it is regulated by the FCA in the UK, it still needs to be authorised by the Bank of France to take orders in CFDs:

The reason for this is simple. Any company offering CFDs in France requires authorisation by the French central bank, be they British or French or whatever. Presumably the fact that CFDs are a leveraged activity means that the Banque de France might want to step in if one of the CFD providers went bust, to prevent any knock on effects on the wider French financial system. It therefore wants to be sure that the CFD providers it is standing behind are not taking too much risk. So although the passport allows IG to operate as a retail financial services firm in France, it has to follow the same rules as all French retail financial services firms, which in this case includes CFD authorisation from the Banque de France. Similarly in insurance, each national regulator has its own, sometimes highly idiosyncratic, capital solvency requirements. Although the passport would allow a UK authorised firm to set up as an insurance company in an EU country, it would still have to hold enough capital in that country to comply with solvency requirements which are set by its national regulator.

For all the general chit chat about the UK benefiting from a single market in European financial services, any examination of the handful of real companies that actually operate cross border in Europe on any scale reveals that the personal savings market in Europe is still regulated at the national level. So much for the famous EU banking passport.

It’s important to bear in mind that not much wealth and not many highly paid jobs are generated by most of these customer facing activities. Pension funds are under pressure to charge as little as possible, and they buy any fund or benefits payment administration in bulk from large providers who charge a low fee on high volume. SIPP providers take an administration charge as well as a small fee for every trade you carry out. It’s a low margin, volume game. The same is true for brokerage accounts, usually minus the admin fees. And these operations are not typically based in the City, but in low cost cities like Glasgow, or regional asset gathering centers. One of the biggest personal investment providers in the UK, Hargreaves Lansdowne, is based in Bristol.

As an aside, the second iteration of the EU’s “Markets in Financial Instruments Directive” (Mifid 2), when implemented (it is currently behind schedule), will give any firm (including firms in the US or Singapore) with “equivalent regulation to the EU’s” access to the single market for financial services products. This would make the EU banking passport irrelevant for the financial services industry – in theory. In practice, with Mifid 2 as with the passport, national regulators will still manage to ensure they are in control. Whatever the case, passport and equivalence are only required for cross-border EU retail activities and these are small

What is heavily concentrated in the City, and earns big fees (and bonuses), is wealth management companies such as family offices and private banks. This is where very wealthy people pay high fees for a personalised wealth management service. Again, this is typically regulated by the FCA or other domestic regulators, nothing to do with Europe. And as these are wealthy people they are typically nimble in moving their money around from one jurisdiction to the other.

[Update 18/3/2019: There are a small number of UK banks which take deposits from EU retail depositors and sell financial products and services to EU SMEs and private banking customers. These activities are responsible for the small (< 1% of total City jobs) relocations due to Brexit as we describe here.]

Once the investor’s money is handed over to the heavily regulated customer facing investment company, regulation becomes much less intense. The customer facing company, because it is a professional entity, is able to invest internationally with a great deal of flexibility and without much interference, as we shall see.

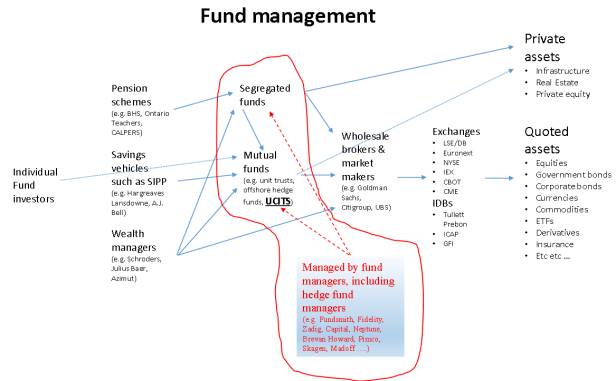

Intermediation, step 2: Fund management – this is where it gets interesting, but not for Europe

As you can see there are two types of funds in the top half of the diagram, segregated funds and mutual funds. Segregated funds are bespoke funds (typically pension funds) set up by the fund sponsors for a particular set of investors (typically employees paying into the sponsor company’s pension scheme). There are other less high profile types of segregated funds that I didn’t put on the diagram for the sake of simplicity; these include insurance funds (e.g. Aviva life insurance), sovereign wealth funds (e.g. Government of Singapore Investment Corporation), trade union funds, university endowments (e.g. Harvard), charitable funds (e.g. Wellcome Trust) and central bank reserve funds (e.g. Hong Kong Monetary Authority). Mutual funds, by contrast, are wholesale or “off the shelf,” rather than bespoke, and open to any investor as long as they meet the fund’s eligibility criteria (money laundering check, minimum investment amount etc.).

It is crucial to note the following fact: these segregated funds and mutual funds are independent entities in their own right. I made a point in the diagram above of separating the fund companies (segregated or mutual) – through which the investor’s money is handled – from the “fund managers” who manage that money (and are highlighted in red font on blue background). This made the diagram more complicated, but was necessary in order to emphasise this important distinction.

Segregated funds (and any sub-funds within them) are set up and administered by the fund sponsors, but independent from those sponsors. They have their own board of trustees, for example, who are there to prevent the fund sponsors from doing anything which might jeopardise the fund’s ability to meet its obligations. As for mutual funds, although most are set up by the fund management companies that manage them, they are nonetheless independent from those fund management companies. Offshore funds such as Cayman Island funds have very little regulation, which is partly why Bernard Madoff was able to run his pyramid scheme in one of them. However onshore funds such as UK unit trusts or UCITS funds (which are crucial to the Brexit debate) insist that the fund company be solidly independent to avoid such risks. Nearly all onshore funds, by law, have their own custodians, who hold all the assets including cash on the fund’s behalf (the charge for this typically varies from one to five basis points or 0.01-0.05% per annum); administrators who value the fund on a daily basis and calculate the value of each investor’s share in it, particularly when the investor adds or withdraws money (this service typically costs 5-10 basis points or 0.05-0.10% per annum); and independent directors who defend the investors’ interests and oversee the fund manager (typically paid £5k-£50k per annum).

These independent (segregated or mutual) fund companies almost invariably entrust the active management of their assets to third party fund management companies (the exceptions are some segregated funds which manage part or all of their assets in house; the Canadian public pension funds are leaders in such in-sourced management). So the fund management companies (the part in red font on blue background in the diagram) are paid a fee by the (segregated or mutual) fund company to manage the assets in that fund. This fee typically varies from 25 basis points (0.25%) per annum for very large pension funds to up to 2% plus 20% performance fee for hedge funds. In other words, this is where the big money is made, in the fund management company, not the fund company itself. In summary, the investor’s funds are held in the fund company. But how those funds are invested is typically decided by the fund management company appointed by the fund company. The independence of funds, particularly of the mutual fund from the fund management company that manages it, is crucial when it comes to assessing Brexit’s impact on the City. The relationship governed by EU regulation is that between the investor and the fund company. But the relationship through which the City makes money is the “business to business” relationship between that fund company and the fund management company it employs to manage its assets.

It is on this point that TheCityUK is highly misleading. It suggests that being part of the EU somehow facilitates the City’s management of “a European fund” (all quotes taken from the “Practitioner’s Guide” pps 6-7):

This is clearly not the case with segregated funds. There is no need to set up a “local office” to manage a segregated fund because the segregated fund has already been set up by the fund sponsor to handle the investors’ money. Once it has been duly established, that segregated fund can appoint who it likes as fund manager. In practice it may take a very cautious approach to avoid reputational risk. Typically the pension scheme will have rules to say it will only select managers who are authorised and overseen by a (national) regulatory body, but that is their choice. Nothing to do with Europe. You can have a Swedish pension fund which employs a US manager, authorised by the SEC, to manage a segregated US corporate bond portfolio on its behalf, or a German pension fund which employs a Chinese manager, authorised by the Singapore monetary authority, to manage a Chinese equity portfolio on its behalf. Large parts of the UK fund management industry manages segregated mandates for US endowments, Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds and Asian monetary authorities’ reserve funds without any of the countries concerned being part of the EU. This is totally international and has nothing to do with EU regulation or trade deals. None of this can change post Brexit.

As for mutual funds, they – as independent entities – are subject to regulations which are totally different from those which apply to the fund management companies that manage the assets in them. Fund managers only need to be authorised by their domestic regulator, but the fund companies need to be authorised in any region in which they are available for sale. In practice, you can find a US fund manager, based in New York and authorised by the SEC, who manages a UK unit trust, a Luxembourg UCITS fund and a US mutual fund. The US mutual fund and fund manager are authorised in the US (though sometimes by multiple and different entities), the UCITS fund is authorised in Luxembourg and the UK unit trust is authorised in the UK.

UCITS: not so much a Brexit risk for the City as a Trojan horse into Europe

Most mutual funds, such as UK unit trusts, used to only be sold in domestic markets where they were regulated by a domestic regulator in isolation. However the UCITS – or “Undertaking for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities” – directives are a set of European directives that allow collective investment schemes (i.e. mutual funds) to be sold freely throughout the EU on the basis of a single authorisation in one EU member state. In practice, most of the growth in mutual funds in Europe, including those managed in the City, is in UCITS funds. The risk would be that post Brexit the City would no longer be able to offer or manage UCITS funds. This risk is highlighted by many, including the UK’s former EU commissioner Jonathan Hill, the Center for European Policy Research (CEPR) and TheCityUK:

However looking at the UCITS legislation in detail you find that these august bodies and individuals don’t really understand UCITS. The UK will indeed no longer be able to issue UCITS funds post Brexit. However, in practice, hardly any UCITS funds were ever issued in the UK in the first place! The City’s business is managing UCITS funds, not issuing them. The vast majority of UCITS funds are issued in Dublin and Luxembourg, where they are approved by the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) and Banque Centrale du Luxembourg (BCL). Large industries have sprung up in these two jurisdictions to support the growth of UCITS funds. The main income generated due to UCITS in Dublin and Luxembourg consists of the costs (mainly legal fees) for setting the funds up (typically £10,000-£50,000 per fund) which are charged to the fund, typically over five years. It is in this activity that the UK might be prevented from participating post Brexit, but it is a small activity and as previously stated one from which the City hardly derives any revenue. The crucial point is that virtually all the UCITS funds managed in the City are issued in Dublin and Luxembourg, which remain part of the EU. As long as the funds managed and generating important fees in the City are approved by the CBI or the BCL and meet the criteria for UCITS, they will continue to be available to investors throughout Europe based on existing European legislation.

So what are the criteria for UCITS, and can any of them prevent the City from managing UCITS funds post Brexit? For a fund to qualify as UCITS a number of conditions are required:

- A prospectus approved by the authorising member state’s central bank;

- A well established investment and risk management policy clearly stated in that prospectus;

- Limitations on total portfolio risk and position sizes;

- Independent Board of Directors, Custodian and Fund Administrator;

- Minimum capital requirement for the management company;

- Regular liquidity.

If you read this carefully, none of these rules require the manager of the UCITS fund to be authorised in an EU member state. For the central bank to approve the prospectus you need, in practice, to be authorised by a competent authority. But nowhere in either central banks’ rule book is there any rule specifying that those competent authorities must be established in an EU member state; fund managers authorised by the SEC in the US or Monetary Authority of Singapore can manage UCITS funds. The BCI’s rule book is clearly written and it is easy to see that it contains no such provision. In practice, you can have a Luxembourg authorised Asian equities UCITS fund managed by a Hong Kong Monetary Authority authorised fund manager.

Indeed, Article 13 of UCITS (p 49) says explicitly, in black and white, that third country fund managers can act as delegated managers of UCITS funds:

UK fund managers will therefore be able to act as delegated managers of UCITS funds when the UK becomes a third country post-Brexit. What the UK fund management industry earned from EU clients were those delegated management fees. According to the EU’s own UCITS legislation, UK fund management firms will continue to earn those delegated management fees from UCITS funds post Brexit. So nothing will change.

If the EU try to change the rules to make it obligatory for managers of UCITS funds to be based in the EU, so as to spitefully prevent City fund managers from managing such funds, they will also have to ban New York, Hong Kong, Melbourne, San Francisco … or else be in contempt of the WTO. The EU would therefore prevent EU investors from investing in US small cap equity funds managed by specialists based in the US, or Chinese equities funds managed by specialists based in China. This would not only damage the prospects for EU savers but also make UCITS as a product category, which the EU is keen to promote with investors outside the EU, less attractive. Moreover these funds belong to investors. If the EU butts in and prevents the company managing the fund from managing it they would be violating those investors’ rights. The EU would face lawsuits of gigantic proportions which it would lose. Given the parlous state of EU pensions, this is a particularly explosive area for the EU to play games with.

Bottom line: post Brexit, City fund managers can continue to manage segregated and mutual funds as they did before. And they can continue – under existing regulations – to manage Luxembourg or Dublin authorised UCITS funds which will be available to investors throughout Europe. There is nothing the EU can do about this.

Intermediation, step 3: Broking – totally international, wholesale market in which (minimal) domestic regulation applies

To buy their assets fund managers typically go through brokers, unless they are buying unlisted assets such as real estate, private equity or infrastructure (which are often sold through agents or corporate bankers). The brokers typically publish research and bring companies to visit the fund managers to justify their (currently shrinking) commissions. In addition to entering orders for customers onto the exchange, or with inter-dealer-brokers (IDBs) for products such as government bonds which are traded over the counter (OTC), brokers will make a market in certain assets, offering to buy them at the bid price or sell them at the offer price, making a spread between the two in exchange for providing liquidity.

TheCityUK highlights a risk to this activity on page 8 of its Practitioners Guide, as does University of Chicago economist Anil Kayshap in “The U.K. Can’t Block Immigration If It Wants To Keep Its Finance Industry,” but again both are very vague regarding how exactly the City would be affected. I don’t think either really understands how markets work. Anyone who is authorised as a fund manager is judged to be able to look after themselves and choose which broker they use. The FCA and other regulators should and do investigate the brokerage firms to make sure they are not up to some skullduggery, such as engaging in insider trading or rigging LIBOR. But the regulator’s aim here is to protect investors, not to tell fund managers in which city their brokers are allowed to operate. In fact, any restrictions regarding which brokers a fund manager can use are token and easy to comply with. In practice, you have French fund managers buying Russian equities through JP Morgan’s Moscow equities desk for their global fund (which may be a Dublin authorised UCITS fund), and the same French fund manager buying a Kazakhstan mining stock through UBS’s London equities desk for the same fund. If a Dutch pension fund wants to buy French government bonds OTC, it may call a broker in London, who happens to have them on offer; if it wants to sell Canadian government bonds OTC, it may call a broker in New York, who happens to have a large bid.

Remember, any trade basically involves an investor (call her Investor A) who owns an asset (call it asset X) and another investor who wants to buy that asset from her (call him Investor B). Asset X is Investor A’s property. It’s her decision whether to sell it – or not. And it’s Investor B’s money. It’s his decision whether to spend it on Asset X – or not. It’s a private transaction. Between two professional investors. The EU cannot tell them what to do with that asset. Or where they carry out their trade.

Bottom line: This is a totally international market where people trade what they want where they find the liquidity. Period. Nothing to do with Europe or any trade deals. Any regulation is there to protect the fund manager and her clients, not to prevent her from using brokers in any particular location. In practice, brokers tend to cluster close to their customers, the fund managers, and this will continue to play into London’s hands post Brexit.

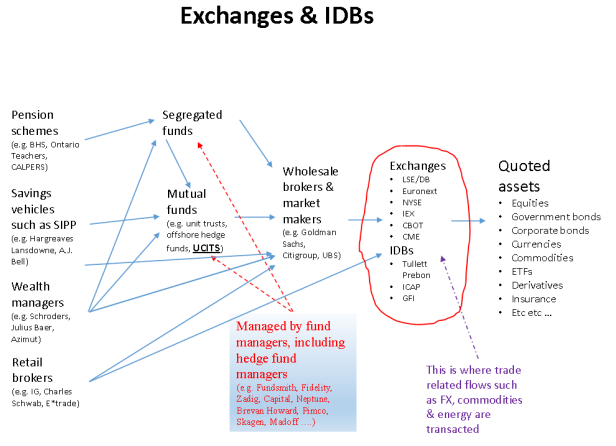

Intermediation, step 4: Exchanges and IDBs – private companies, totally international, can trade what they want with whom they want

Stock exchanges and IDBs are basically utilities which charge a small fee to allow trades to be matched. They are privately owned and make decent profits for their owners. And those owners are spread throughout the world: most Deutsche Börse shareholders are also LSE shareholders, and a large percentage of them are neither based in the UK nor in Germany. But the LSE and other exchanges don’t employ that many people nor contribute that much to the economies of the countries in which they are nominally based. However a lot of the vague threats made about the City seem to concern these private utilities. Anil Kashyan writes: “swap contracts that are denominated in euros are a trillion-dollar market, and most of that business is now centered in London. French President Francois Hollande has said that this activity should be moved back into the EU.”

It is one of the most ridiculous aspects of the debate regarding the impact of Brexit on the City that people taking part in it assume that governments decide on what exchange (or with which IDB) any financial instrument is traded. Since when has this ever been the case? Can anyone name one exchange or IDB in Europe which was set up by a government? Imagine a five year Euro Swap paying a fixed rate in exchange for receiving 3 month euribor. Most Swaps are not even traded on exchanges but OTC, like bonds and currencies. To trade OTC you basically need a phone, a computer and a list of clients. Now imagine an IDB in London offers a market in such a 5 year Euro Swap. Some brokers buy it on behalf of their clients, who thereby agree to receive the fixed rate and pay the floating rate (3 month euribor), some brokers sell it on behalf of their clients, who agree to pay the fixed rate and receive 3 month euribor. Effectively, the Swap trading facility managed by the IDB is like a betting operation. If offers a bet on interest rates which it continually prices so that both sides of the book, those betting on increasing and decreasing interest rates are balanced. In other words, it is providing an automated facility through which different banks can bet on interest rates on behalf of their clients against each other. The term “bet” may seem pejorative, so it is important to note that these transactions are often based on rational business needs, for example a mortgate bank “betting” on an interest rate rise by buying an interest rate Swap may be insuring itself against a rise in interest rates impacting its margins on the fixed rate mortgages it has written, while the pension fund writing the interest rate Swap may be gaining a long dated fixed income stream which matches its long dated liabilities.

Banks and can and do enter into such transactions with each other all the time and all over the world. Their ability to do so is essential to the smooth functioning of the financial system. These are bilateral transactions between big investment banks over which the EU has no say. If investors decide to trade Swaps through banks in London, what on earth is François Hollande going to do about it? Cough, tap them on the shoulder and say “mes amis, you must not do zis in Londres”? This is global finance, not some 80s sitcom. The Swap is a bilateral contract between two parties taking different views on interest rates. Those parties can take these views with any IDB or exchange in any city they want. The only things those parties care about are liquidity, price integrity, speed of execution, counterparty risk, the legal status of their contract (UK contract legislation is prized throughout the world) and regulation (the EU’s approach to regulation is loathed by traders throughout the world). What François Hollande or any other European politician may think doesn’t even make the list.

Turning to equities, if the French fund manager we discussed above wants to buy a Russian stock he may be able to buy it on the Moscow stock exchange or the LSE; often they are dual listed. It’s up to him where he buys his stock, up to the company where it lists its stock, and up to the exchange whom it admits for listing. These are private companies, as the merger of Deutsche Börse and LSE post Brexit and the merger of the Nordic OMX with Nasdaq many moons ago eloquently demonstrated. Often you get many exchanges competing for liquidity in the same stock – Nokia for example is actively traded in the US, Finland, Sweden and Germany. Unilever is quoted in London and in Amsterdam. Signet is quoted in London and New York. Shares of the Italian fashion house Prada are exclusively traded in Hong Kong!

If Prada can be quoted and traded in Hong Kong, how on earth is the EU going to stop anyone trading anything in London? Who do you think you’re kidding Mr Junker?

Bottom line: anyone who wants to and is authorised by an exchange or an IDB can trade there if they’re an investor and be traded there if they’re an issuer. It’s the exchange or the IDB’s exclusive decision. No trade deals needed. The EU has absolutely no say in any of this. Never had before Brexit. Never will after Brexit.

Corporate finance and proprietary trading

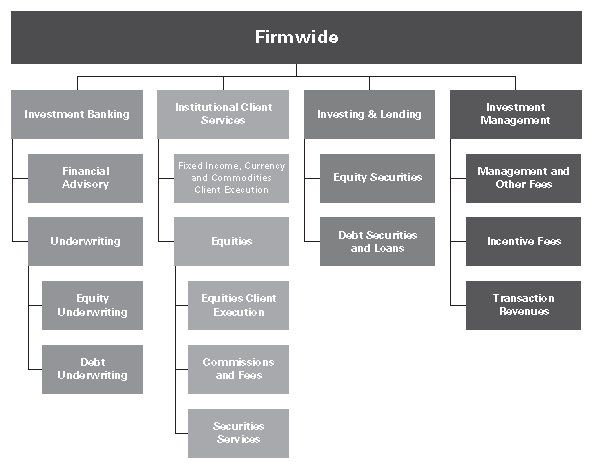

To round out the list of activities carried out in the City we need to look at two other activities not directly related to managing financial assets. To satisfy ourselves that we are covering all the bases what better place to look than a list of Goldman Sachs’s activities, taken from their annual report 2015 (page 13). After all, the EU officials, central bank governors, IMF managing directors and other grandees warning about Brexit were to a large extent former Goldman employees.

“Institutional client services” basically means what I prosaically describe as “broking” in the sections above. “Investment management” is what I call “fund management.” So those two are covered.

“Investing and lending” is activity carried out with Goldman Sachs’s own balance sheet. A large part of this is proprietary trading or “prop trading,” where Goldman takes punts on various markets with its own money. There is nothing the EU can do to stop Goldman doing this from London. Japanese and German banks (many of the latter, ironically, owned by the German regional governments or Länder) for example have big prop desks whose ability to lose money on any exchange or OTC market in the world – London, Hong Kong or New York – is legendary. If the exchanges or IDBs in London (or indeed anywhere else) are happy to deal with prop traders anywhere in the world there is nothing the EU can do about it. Remember, it’s Goldman’s money that Goldman is playing with. If Goldman’s prop desk in London thinks it’s a no brainer to go long a five year Euro Swap, and BNP Paribas’ prop desk in New York thinks it’s a clever idea to go short the same Swap, what can the EU possibly do about it?

Goldman’s loans are typically to large companies that can borrow anywhere they like. As long as Goldman as lender approves them and they are not breaching any domestic leverage rules no regulator can stop them. Move on. Nothing to see.

Investment banking, which refer I to as “corporate finance” above, is a more interesting case. Here, a company or government that wants to issue equity or debt will pay Goldman (or its oleaginous competitors such as Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, UBS, JP Morgan etc.) to value the business, produce a prospectus, organise roadshows and place the shares through its own sales force and various other brokers. The issuer may pay an underwriting fee, against which Goldman (or one of its oleaginous competitors) promises to buy any securities which can’t be placed with investors, thus guaranteeing the issuer will raise the funds it needs. Investment banking also comprises giving companies advice (for large fees) on corporate activity such as mergers and acquisitions (M&A), spin-offs, debt restructuring, tax driven corporate inversions and the like.

This is a highly international market in which the customers are big corporates and governments. If Saint-Gobain thinks that JP Morgan’s corporate finance desk in London will get their emergency rights issue away it’s up to Saint-Gobain. If the Italian government thinks UBS’s corporate finance desk in London can get its emergency bond issue away that’s the Italian government’s decision. And, let’s face it, if they’re desperate for cash, a big firm in London will reassure the international investors (who, remember, have to buy the paper they issue) more than any local French or Italian firm!

Brass plaques – circumvent any legislation

Money is in essence immaterial. It can move around the world at the push of a button. The only tangible assets in the City are expensive art work and computers, which can pretty much sit anywhere. Anyone wanting to circumvent any European directive which requires them to operate from an EU jurisdiction can easily conform with that directive by opening an office with a desk and two secretaries. Not that I think they would need to since, as already explained, most if not all of the City’s activities are not EU regulated.

Let’s imagine that there actually was a rule that forced all fund managers, for example a US bond fund management firm like Pimco, who manage funds for EU clients to have an office in the EU. And let’s imagine that Pimco currently has an office in London to meet that requirement. Post Brexit, the UK is no longer in the EU, so Pimco can’t use its office in London to meet the requirement and has to open a new office in the EU. In other words one of the Brexit scare stories comes to pass. What changes? Pimco opens an office in Estonia, with a desk and two pretty Estonian secretaries, and pays €20k in rent. But the fund managers earning big bonuses for managing the fund are still based in Newport Beach, California (as they were when Pimco’s “EU office” was in London). And the profits made from the fund management fees are still being earned by the Pimco LLC in the United States of America (just as they were when Pimco’s “EU office” was in London). The transfer of value from London to Estonia has been two secretary salaries and a €20k rent cheque. In other words the square root of nothing. It would be exactly the same for a fund management firm based in London as it would for Pimco based in Newport Beach. Because finance is international and intangible, the only parts of it that the EU can hope to control are the parts that have no value.

European banking passport – a red herring

The European banking passport allows banks in one member state to offer “banking services” in another member state. Banking services essentially means issuing credit cards, granting loans and mortgages and taking deposits. The sort of thing the TSB or the Co-op Bank do in the UK. The best example of the banking passport in the UK is Sweden’s Handelsbanken, which is growing very rapidly in small business banking. However the City doesn’t really do this, it’s not a big part of its activities. Note that Metro Bank, based in the USA, is growing a retail banking franchise in the UK at a similar rate to Handelsbanken’s SME franchise, despite not enjoying a European passport. If UK banks really, really, want to operate in retail banking in the EU they can easily obtain a banking license in whichever country they choose, just like Metrobank did in the UK.

Euroclear – a risk

Exchanges and IDBs match buyers with sellers instantaneously, and rely on those parties to settle their bargains in good faith, on T+1 or +2 or whatever. Clearing houses facilitate this by guaranteeing the settlement of the trades, so traders can trade without fear of being “welched on,” and in return take a small clearing fee and ask the traders to post collateral. Because many traders will be buying and selling the same securities at any point, a clearing house can “net” these flows off so they are only exposed to a small volume of completion risk at any one time. This enables them to minimise the capital demanded from traders.

LCH Clearnet in London is just such a clearing house, and one of its major activities is clearing Swaps. The fact that this activity may be endangered by Brexit is often alluded to (see FT Alphaville) without really explaining the source of the problem. To understand this issue we need to revisit the Swaps market, described above, and in particular understand the source of the underlying demand for Swaps. The typical user of a Swap is a deposit funded bank that writes a lot of mortgages. Such a bank will typically derive the vast majority of its funding from customer deposits, on which it pays a floating rate (for Eurozone banks this rate tracks euribor). If it writes its mortgages at floating rates then it doesn’t need any Swaps. However many of its customers will want to fix their borrowing costs. Moreover, if its borrowers have variable rate mortgages and floating rates rise those floating rate borrowers’ monthly payments will increase and their ability to service their debts will be impaired, potentially leading to defaults. So banks are often keen for borrowers to fix their mortgages in order to minimise credit risk. But when such banks write fixed rate mortgages which are effectively funded by floating rate deposits, they end up with an interest rate mismatch. If floating rates fall then their margins increase, but if rates rise their margins reduce and, at a certain point, go negative. This is a serious, potentially fatal risk for any bank. Such banks therefore “hedge” this interest rate risk by going into the Swaps market and swapping their borrower’s floating rate into a fixed rate at the current Swap rate – of course after slapping a mark-up onto the fixed mortgage cost they charge their customers (“passing currency from hand to hand …”).

On the other side of the trade is, as described above, an entity that wants to receive a fixed rate and pay a floating rate. This might, in theory, be a bank with an excess of fixed rate deposits, but in practice such entities are rare as hens’ teeth. In reality, the other side of the trade is usually a financial investor who is looking to earn a premium. As the fixed rate is almost invariably above the relevant floating rate, anyone writing a Swap will collect a spread, in other words will earn a positive “carry” as long as floating rates don’t rise too much.

If you take a step back, the Swaps market is very similar to insurance. Those buying the Swap pay to “insure” themselves against rising interest rates. Those writing the Swap are being paid an annual premium to provide that insurance. If floating rates rise it reduces the Swap writers’ income and at a certain point turns it negative, meaning they have to pay out – just as your car insurance company does when you have a crash. Now if you cast your mind back to the last major financial crisis, as described in Michael Lewis’s brilliant The Big Short (2010), you will remember that one of its major contributory factors was just such financial insurance products. And that those products were also a kind of Swap. At the epicenter of the last crisis were sub-prime loans, effectively mortgage loans to borrowers who were too poor to afford the houses they lived in, and which would turn sour if property prices ever stopped going up. Naturally, there was great demand for insurance against defaults on the various classes of sub-prime debt from a number of entities: the banks writing the mortgages, financial institutions to whom those mortgages were repackaged and sold in the form of CDOs, CLOs etc. and, crucially, the heroes of The Big Short who thought the whole thing was a fraud. These entities went into the credit default Swap (“CDS”) market either to hedge their credit risk or (in the case of the heroes of the Big Short) to make money when the house of cards collapsed.

On the other side of that trade were the villains of The Big Short, insurers like AIG and Wall Street brokers like Goldman and Morgan Stanley who thought it was easy money to take juicy premiums against the risk of sub-prime default – a risk they underestimated. When property prices eventually stopped rising and mortgages on variable rates (“ARM”) with two year teaser rates re-set to higher market rates, mortgage defaults exploded and a lot of the CDS “credit insurance policies” were triggered. The problem was that the companies writing the insurance turned out not to have nearly enough capital and were therefore unable to pay; they were caught with their trousers down. There was a domino effect, as Wall Street bank A had bought insurance from Wall Street bank B, but Wall Street bank B couldn’t pay out so Wall Street bank A couldn’t make good on the insurance it had sold to Wall Street bank C, and so on. Two early casualties of this hot mess were Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. As Warren Buffet succinctly put it with his usual barbed wit, “when the tide goes out you discover who’s been swimming naked.” The great scandal was that these firms were allowed to make lots of money writing insurance on dodgy sub-prime loans during the boom, and were then bailed out by the Federal Reserve when they weren’t able to pay out on their stupid bets in the bust. The Fed effectively waded out into the sea and handed Wall Street a towel. It makes you weep.

Turning back to the Euro interest rates Swap market, if we ever have a rise in interest rates, the European mortgage bank which used to sleep soundly at night in the knowledge that it swapped (or insured) its interest rate risk doesn’t want to wake up in a cold sweat because the other side of the trade, who wrote the Swap, isn’t going to pay out – just as the Wall Street banks and AIG couldn’t pay out on their credit default Swaps during the sub-prime fiasco. As I explained above, as interest rates rise LCH Clearnet will be demanding more and more capital from the investor who wrote the Swap. If that investor can’t post the collateral then LCH will close the position at a loss for the investor. All its collateral will be used to make good on the “insurance policy” it wrote. But as interest rates rise further that capital will be eaten up.

This is where the ECB starts to get worried that we get a repeat of a scam like the one perpetrated in the sub-prime bubble. It may fear that City investment banks and others will make a lot of money in London writing Swaps in the good times, but not hold enough capital to make good on the insurance they promised if interest rates ever rise. And if the interest rate insurance purchased by European banks doesn’t pay out the ECB will be left holding the baby. The banks with fixed rate mortgages and whose Swap counterparties have defaulted will be hit by rising interest rates and/or increased defaults. This could rapidly make those banks insolvent. Any other bank with exposure to such banks will be at risk and seek to withdraw its deposits. But, just like last time, no one will really know who is at risk, everyone will deny everything, the rumor mill will go into overdrive and confidence will evaporate. You could easily have a domino effect similar to the one which brought the financial system down in 2008, leading to another run on the banks. The ECB might end up in the ignominious position of having to bail LCH out to stop the European banking system from collapsing. Like Wall Street in 2008, the London banks would have made money in the boom and been bailed out (by the ECB) in the bust.

This is far from being a theoretical risk. The parallels between the current interest rate situation and the housing boom that preceded the 2008 crash are frankly spooky. Central bank interest rates and government bond yields have been steadily declining since the 2008 crash to the point of being negative in real terms in many countries; such low rates have no historical precedent. Financial leverage in the housing market and house price (un)affordability reached similarly unprecedented levels before the last crash. The one way direction in which interest rates have moved has left large parts of the financial industry totally unprepared for and vulnerable to a rise in interest rates, just as the one way rise in property prices did in the 2008 crash. So you can understand why the ECB might be worried.

Because of these risks, European banks may be reluctant to trust a Swaps clearing house that is not backed by the ECB. So for LCH Clearnet to continue to clear Swaps post Brexit it may have to be regulated by the ECB and in particular require leverage ratios from its clients and implement collateral policies which reassure the ECB that the investment banks playing in the Swaps market are not taking the piss in the way Wall Street did during the sub-prime debacle. In fact, LCH is already regulated by numerous European regulators, including France’s Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel (the same one that regulates IG!). LCH could of course open an office in Frankfurt in which all its regulatory, client approval, risk assessment and collateral management functions were performed. This would allow the IT and sales functions to stay in London. But the ECB may insist that everything moves out of London. It’s a hard one to call.

All that said, this is a relatively small part of the wealth generated by the City and the impact would not be significant. The important point is that there is no read across from Swaps clearing to the rest of the City’s activities. The robustness of Euro denominated Swaps clearing is important for the solvency of the European banking system. ECB support is therefore likely to be demanded by the Swaps customers. None of this applies to the City’s other activities.

“But why are the banks warning about job losses?”

Many of the City’s activites are under immense pressure, and have been long before Brexit:

- There is much less money to be made in prop trading with volatility at low levels. What’s the point of taking a punt on an asset when the central banks are dictating its price?

- The blow up of Lehman rightly encouraged regulators to force banks to hold much more equity against those (currently less profitable) prop trading activities, making them even more burdensome to maintain.

- Brokerage fees are under relentless pressure. Fund managers used to cover the costs of the broker research they used with the commissions they paid to those brokers for trading stocks. Effectively the client was paying for research the fund manager was using to do the job … for which it was already charging the client a fat fee. New standards limit this, forcing fund managers to scrutinise the amount they pay for research and putting pressure on brokerage fees.

- More and more funds are passive funds that mirror indices and only trade when there is a change in the index they track. These passive funds accordingly trade less often than active funds, and they also comprise an increasing proportion of the market, all of which is reducing trading volumes.

- Fund management fees are under pressure due to having been too high to begin with, the poor performance of many fund managers against the indices they are supposed to beat and competition from low margin passive funds which track those indices.

Just look at the share prices of Barclays or Deutsche Bank if you don’t believe me. Admitting this is of course somewhat humiliating for the investment banks’ big headed CEOs. Brexit provides them with a convenient way to shrink without admitting failure.

The Upside – Leck mi am Arsch!

The much lamented Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (800-1806 AD) was a loose collection of independent states and city states. It was a model of the kind of minimalist federation which might have actually worked for the EU, rather than the centralising, maximalist model (based, it seems to me, on the French Revolution) which has made the EU fail. One of those independent city states, a town in the west of that former Empire, has at its entrance a tower referred to as the “Leck mi am Arsch” or “kiss my ass” tower. That independent town was, for centuries, open to all sorts of people who were persecuted in nearby France and elsewhere in the Empire, such as Jews (the town’s synagogue survived WWII), Protestants or Freemasons. As they walked under the tower they could turn to any of their persecutors who were in hot pursuit, and proffer the words for which the tower is famous without any fear of retribution. I love that.

Europe’s attempts at uniformisation have progressively eliminated such places of refuge. And Europe, with its attacks on bonuses, its desire to impose a transaction or Tobin tax and its other meddling attempts at micro-management – which encouraged people to vote Brexit in the first place – is giving more and more businesses, particularly in finance, the wish to flee to a place of refuge. London post Brexit will be such a place. A place where bankers, hedge fund managers, traders and all sorts of wealthy people fed up with the EU’s meddling will be delighted to find sanctuary. A place where they can safely turn around and say to the EU: Leck mi am Arsch.

Any questions, objections or comments please be forthcoming. I always respond.

A very helpful and illustrative description of the City workings, thank-you.

LikeLike

Thanks a lot Penelope, very kind of you to comment so generously. Makes it worthwhile doing the work.

LikeLike

Very interesting article even from a laymans perspective. Do you have a view why the points you make are being ignored or even actively dismissed by the media or Remoaners?

As the many of the mechanics you outlined are outside the competence of governments/structures involved in Brexit negotiations when will the realities kick in and commerce break cover and tell the politicians that they are not dealing with reality?

Finally are the UK media taking are cognisance of your views or does it go against their political bias?

LikeLike

Hello Suttongers

Thank you very much for reading and commenting. Means a lot to me to have such intelligent and thoughtful readers.

As a European living in the UK I feel very defensive of a people who have been so welcoming and so fair to me. Readers like you exemplify this British spirit of which I feel so defensive and which in part motivated me to write.

The media is very biased, including parts of the BBC. The ignorance and dismissal you rightly point out is part of this “fake news” agenda. Also, as I mention in the blog, many people in the media don’t understand the City or its intricate workings. Relying on the easy “banking passport” headlines served up by the pro Remain empty suits in the City is much easier than reading and researching.

When will the realities kick in? I suspect that will happen when the negotiations start to reach conclusions. Looking at the broader picture, what puzzles me is why the empty suits at the top of the City keep telling lies about what the impact of Brexit will be. Your questions and those of others have kicked me in the backside to write a much shorter piece on that topic which I shall post soon. Thanks again Sir.

SF

LikeLike

Interesting article thank you. Just a couple of points, it is not quite rights to say that UCITS management companies do not have to be established in a member state. In fact they do, but they are able to delegate certain activities (in particular actual fund management) to entities located outside of the EU, subject to conditions. The authorisation of banks and investment firms is also a bit more prescriptive than you suggest, even for wholesale clients. You may find this paper interesting: http://www.li.com/activities/publications/special-trade-commission-financial-services-briefing

LikeLike

Hi Victoria, thank you very much for your comment. I just want to be clear I understand you. My point was that the UCITs companies need to be based in the EU but the companies that manage them don’t. So it depends on what you refer to as the “UCITs management companies.” In the helpful Legatum Institute piece for which you provided the link on page 72. Here it says the UCITS company (i.e. the fund which holds assets on behalf of the investor) can be self managed. In other words you don’t need a UCITS management company. The self-managed UCITS fund can simply delegate management of its assets to a third party fund manager as long as “the delegate is authorised and supervised in its home state.” So what Legatum says about fund management and UCITS seems to me to be entirely consistent with what I said. In my piece I didn’t discuss banks as there is very little cross-border banking, and, where there is, it is mainly due to acquisitions, in which the acquirer acquired a domestic banking license by virtue of which it can act without any passport. As for investment firms, I’m not sure what you mean by “more prescriptive.” Specifically, how might these more prescriptive regulations prevent a City based fund manager being paid by a UCITS company (i.e. UCITS fund) to manage the assets in that company/fund?

Thank you again though for taking the time to read and respond. Look forward to hearing from you again.

SF

LikeLike

Hello, A very interesting article but there are a number of inaccuracies which need to be fine tuned. One of them is the ability of this country firms to access the EU in a manner that is implicitly equivalent to passporting. This is wholly inaccurate. Equivalence may apply for specific matters like price transparency and venue trading but it’s pretty limited

“As an aside, the second iteration of the EU’s “Markets in Financial Instruments Directive” (Mifid 2), when implemented (it is currently behind schedule), will give any firm (including firms in the US or Singapore) with “equivalent regulation to the EU’s” access to the single market for financial services products.

LikeLike

James, thanks for reading. I never talked about “access implicitly equivalent to passporting. I mentioned “equivalence” as one of the solutions, but my point is that isn’t needed for wholesale financial services. That point has since been confirmed by industry leaders. You mention a number of inaccuracies, but you only give one example. Do you have any others? Happy to discuss. SF

LikeLike

What a brilliant comprehensive piece.

I think it very important that the Dept for Exiting the EU are aware of these points, I shall email them David Davis a copy with your permission.

LikeLike

Mark, thank you so much for this accolade. I think Davis is the greatest prime minister the UK never had. Will be thrilled if you can pass this on to him and I hope it’s useful to him. Thanks again, SF

LikeLike

As a part European who has made a life in this country and benefited from the UK’s flexibility and above all fairness, I hope this work can be helpful to a people toward whom I am eternally grateful

LikeLike

Mark, for some reason many more people than usual seem to be reading my blog, especially the City Brexit post. Would you be so kind as to let me know how you became aware of it? If from twitter, on whose timeline did you see it? Thanks, E

LikeLike

I, for one have shared it on my own twitter account -https://twitter.com/TheScepticIsle:

And my organisations accounts:

https://www.facebook.com/con4lib/

Also see:

Roland Smith https://twitter.com/rolandmcs

Paul Reynolds https://twitter.com/paulrey99

Mr Brexit https://twitter.com/MrBrexit

And others. We all thought your blog was very interesting. Good work.

LikeLike

Thanks Sir, I didn’t get notified – it wasn’t linked to my handle. You have a big following! Thanks a lot. Much appreciated

LikeLike

SF, your blog was also shared here [https://twitter.com/becksv8/status/1015172547414056960] which I think drew a lot of attention, since the commentator himself is both well-followed – and was re-quoted by others (and I confess I have quote them – and hence you – also). As others have said, thanks for your powerful inside narrative, it is very important for people to hear.

HUGE amounts of hot air circulates in #brexit discussions, and real-world commentary like yours is SO important to combat it.

LikeLike

Hi Mike how are you? Thanks for the flag. I’ve sent Martin a message to thank him for the citation. Are you on twitter?

LikeLike

How do you know this information is fact and not opinion?

LikeLike

Everything here is based on legislative documents or market data. So the fact that Italian company Prada is quoted in Hong Kong can be found from the Hong Kong stock exchange. Swaps dealers in London such as Tullett Prebon or GFI similarly publish trading data. The fact that these markets were set up independently of governments is based on negative evidence, no government has started any of these exchanges or IDBs. The info on the UCITs funds can be found in UCITs documentation. The separation of funds from fund managers is observable in the prospectus of every mutual or segregated fund. Etc. etc. etc. etc. If you have a specific question I can point you to further info. But all of this is based on fact, except specific points which I highlight as my forecast, notably regarding Euroclear. Hope that helps.

LikeLike

I have been so fed up with negative posturing on this whole issue and how refreshing to be given facts.

Interesting that you praise Davies when others trash him as a lightweight.

Insightful and intelligent read.

Thank you!

LikeLike

Alastair. Thank you very much for taking the time to read and for your very kind comments. I really like Davies. He’s for small government and he’s anti-censorship, bravely so. And he’s against the idiotic foreign intervention which has caused so many disasters and been advocated by establishment Labour (Blair) and Conservative (Cameron) politicians alike. People who call him lightweight are establishment types who find the truth uncomfortable and can only resort to facile ad hominem. They are the light weights. Do you work in finance or a related area?

LikeLike

This was extremely informative and obviously involved real work on your part. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much Darnell. And, if the “Celt” in your wordpress name means you’re a fellow Celtic supporter, hail hail.

LikeLike

What an excellent article and what a helpful explanation of some very complex matters. I won’t claim I have grasped it all at my first sitting, but I have grasped some of it much better than before. I shall bookmark this and return to it. Thank you very much, SF! Great to have you on our side.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much Lamia, that makes it all worthwhile. My twitter handle is @semperfidem2004. If there’s anything you find hard to understand – it’s because I haven’t explained it well enough, so feel free to ask any questions. One of the many problems with the Remoaners is they’re obsessed with looking clever rather than understanding. So they’re too embarrassed to ask questions, particularly about the many incoherent points made by the so called experts they admire, in case it might make them look like they don’t understand. As for being on your side, the irony is I’m European, and used to be very pro-EU. I call it as I see it, and I can’t support the EU any more. My pet hate is the way the Remoaners look down their noses at the Leavers. Sickens me. PS: I got a lot of reads today for some reason. Can you tell me how you found this piece.

LikeLike

Hi Semperfidem,

Thanks for your reply. I had thought I had read your article through City AM somehow, though it is possible it was via the comments on the website Guido Fawkes, which does a fair of coverage of good Brexit economic news (which of course you hardly find elewhere. I had lost your article, and had been looking for it fruitlessly, but am glad to say I’ve found it again today via Guido Fawkes again. This time it’s being properly bookmarked!

I wish your work was more widely known and from now on I will be linking to it where relevant. All the best.

LikeLike

Hey thanks. Didn’t realise I made it onto Guido! That’s a big upgrade for little me. Would you mind sending me the link? I’m @semperfidem2004 on twitter or you can post it here. Thanks again, SF

LikeLike

Absolutely excellent ! Perhaps you’re too young to remember but in the 80s Cedel and Euroclear did all the T + 2 settlements for Eurobonds. When Brexit happens, the City will accelerate as it did when the US put an interest equalisation tax on American citizens owning foreign shares – and the Eurobond market was born with the clever minds of Armin Mattle, Stanley Ross and a few others. The City never looked back. We were all threatened by Brussels that the euro would destroy the City and that Deutsche Bank would up sticks and go back to Frankfurt but we all laughed as anyone will know, trying to find a dealing price after 5pm local time on Thursday or Friday after lunch on the Continent is wishful thinking.

“Bring it On Brexit” should be the mantra.

LikeLike

Haha. I’m no too young to remember at all. In fact that’s an excellent point which I’ve alluded to many times on twitter without the fascinating detail you’ve provided. The Eurobond market was born of regulatory arbitrage as much in the City was. A distant parallel is the move of listings to London after Sarbannes Oxley. In that respect, the big potential threat to the City is the potential removal of Dodd Frank in the US. If Dodd Frank goes, the UK will have to respond with its own deregulation, and there’s not a chance in hell it can do so from within the EU. I’m delighted by your comment. You should contact me on twitter, quite a few of us discuss these things there. Thank you again for your comment

LikeLike

As a complete layman, this is the article I have been looking for to help me understand the arguments surrounding Brexit and the City. It makes a fascinating first read, but I shall hang on to it and study it in more depth too. Thank you very much for the time and effort you have put into writing this piece and enhancing understanding of the issues.

LikeLike

Hello Lindsey. Thank you very much indeed for those kind words. I wrote it to be helpful so I’m delighted if you find it so. My twitter handle is @semperfidem2004 If there’s anything you don’t understand – it’s my fault for not explaining well enough. So don’t hesitate to ask. Anything you disagree with, likewise, that’s how I learn. All the best, SF

LikeLike

Great article, but can I ask if you could reference that the City’s principal activity is is to manage financial assets? Where did you get that stat? The argument you’re making hangs in large part from that statement so I think it needs a reference. I hope you’re right, because we’d still be able to get UCITS accreditation post-Brexit and then there’d be little impact on our position.

LikeLike

Martin, thank you. You’re right that sentence is a little cursory. Fund management is the City’s main export to the EU, through UCITS. Oliver Wyman have a decent table on page 4 of this otherwise very poor report which is helpful: https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwiehNOB_pXYAhWKYlAKHZPbCgIQFggpMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.oliverwyman.com%2Fcontent%2Fdam%2Foliver-wyman%2Fglobal%2Fen%2F2016%2Foct%2FBrexit_POV.PDF&usg=AOvVaw026cAa-UgS2OX6KPjILedU

LikeLike

Thanks for the quick reply. Looking at figure 3 on page 6 shows relatively little revenue with the EU for asset management, at £5-6bn, and the biggest is ‘banking’ at £23-27bn?

LikeLike

Yes, that banking figure covers a multitude of sins. I analyse it in a post to be published. Of that £25bn c £14bn is interest income and fees from EU banking customers. My analysis, using BIS data and over 25 reports and accounts plus silo accounts, Pillar III and EBA disclosures, shows the income at risk is only £6.3bn, and most of that that can be easily kept by establish a deposit taking subsidiary in the EU. £7bn is sales and trading which, as I said, cannot be blocked by the EU and for which fund management is the magnet. Thank you for being such a careful reader. I wish more people could be bothered to read the sources like you are. Any questions or criticisms please shoot.

LikeLike

In it they estimate £20-23bn revenues from asset management, exceeded by £58-67bn retail and business banking, £30bn sales and trading and £27-28bn domestic and commercial insurance. These are total revenues, not just EU. So retail and commercial banking includes domestic mortgage income. Similarly, personal and commercial insurance income is mostly our car insurance or the local restaurant’s fire insurance. Looking at exports to the EU, I have analysed OW’s £14bn estimate of EU retail & commercial banking income. Only £6.3bn is affected by the passport and the fix is very simple. In the post I explain that wholesale trading in London cannot be stopped by the EU. Neither can corporate finance. So the key is fund management. Fund managers are the traders’ customers, so if they stay in London so will the traders. However, I think your point is valid. I used the phrase to set the scene for a generalist reader but your comment makes me think it was too vague. Thank you very much indeed for the feedback.

LikeLike

Any questions please send me a tweet @semperfidem2004

LikeLike

A fascinating explanation of the “City”. Relatively simple to understand but I will probably need to read it a few times. Many thanks for taking the time to write this in words that mere mortals can understand.

LikeLike

Hi Chris, thanks a lot, very kind of you to say so. Finance can be a little abstract, but it shouldn’t be beyond the wit of man to explain it terms a non-specialist can understand. If there’s anything you don’t understand it’s the fault of my explanation. Any questions send me a tweet: @semperfidem2004

LikeLike

I loved this! I wish I had seen it when you first published as it would have short circuited many an argument I have had on the topic. This piece widely circulated should pull one of the last remaining plugs out of the Remoaner dyke. I followed a link from a comment on a BBC item today to get here, link below. That should help spread the word a bit more. Thanks for the time, effort and wisdom that went into this post.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-43321715?postId=129894908&initial_page_size=10#comment_129894908/13

LikeLike

Hi there John. Thank you so much. It really makes my day to think that people find my work useful. I’m a European citizen living in the UK but very supportive of my British hosts, who have treated me very well, in their attempts to Brexit. Thank you for linking to that BBC discussion. If you have any questions best place to contact me is twitter. My handle is @semperfidem2004

LikeLike